Two Perspectives on Design-Based Research

Melissa and Luis bring their perspectives to design-based research. Should it exist? What is it good for?

On February 19, 2021 at 1 PM MST, we will discuss design-based research in our Talking About Design meeting. If you’d like to join, submit an interest form here and we’ll send you the link!

To prepare for this discussion, Melissa and Luis each provide their perspective on design-based research and implications for research in design and education.

But first, a quick overview:

Melissa: Should DBR Even Exist?

That video was great and all. But can you really use what happens in a specific context to produce a theory that holds across contexts? And if you create something to test a theory that you believe is universal(ish), is that really design?

Let’s start with what design is, then we can consider design-based research (DBR). As I have written in the past, design is about the particular. It takes place through an inquiry Process not unlike scientific research. However, design inquiry is not about finding context-free “truth” or general theory. It is about developing a theory of a unique case, and the resulting theory is heavily context-dependent. The result is a “structure adapted to a purpose” (Perkins, 1986).

Consider these doorknobs:

Each is created to open a door, but each vary in material, shape, style, etc. They are adapted to fit a particular context: does the door need to lock? What stylistic elements work best given the door it is placed on? What should it feel like to open the door? The doorknobs do not offer concepts that are appropriate in all contexts; they are particular conceptualizations for particular contexts.

We can contrast the particular with what Nelson and Stolterman (2012) called the “universal and true,” or something that is meant to apply across multiple contexts. The universal and true strives to be the one and only truth, whereas the particular and “real”—the goal of design—is just one of many possibilities. Thus, Nelson and Solterman described:

Design is a process of moving from the universal, general, and particular to the ultimate particular–the specific design (p. 31).

Important to our discussion here, design integrates the universal and general, but it adapts to the particular.

Donald Schön (1983) presented a similar argument when he claimed that in design, we are developing a theory of a unique case. We are trying to understand the specific thing we are designing in the specific context. He contrasted this with scientific understanding which focuses on generalization.

So, given design’s focus on the particular, how can design inform theoretical knowledge—concepts that transfer across contexts? If design is about moving from the general to the particular, can design also be a tool to move from the particular to the general?

Design scholars often say that design is simply a different form of knowing than science. Thus, design cannot be used to create scientific understanding. However, I believe we regularly use design to create scientific understanding. For example, experiments in physics or psychology are designed to highlight or isolate a specific variable or illuminate a theory. Experiments are particular, real activities that support the understanding of the general.

This is not to say that DBR is simply experimental research (though the introductory video did lean a bit that way). First, a DBR design or intervention must work in a complex context such as a classroom, not in a controlled laboratory. Second, the designs that are often explored in DBR are not only created to test a theory or idea, they also are created to support learning in the context in which they are implemented. This requires more adaptation and nuance than a laboratory experiment.

I believe DBR has the power to impact both local context and broader theory. However, we must carefully consider the types of knowing we are producing and remain sensitive to the fallibility of the resulting theories. We must recognize that, in the end, we are designing theory (Warr et al., 2020), not searching for universal “truth”.

Luis: Why DBR Exists

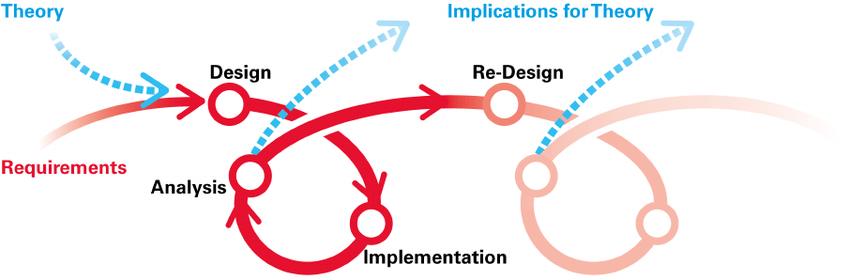

Design-Based Research (DBR) is an approach to organize and carry out research to develop theoretically-driven and evidence-based learning and teaching environments (Design-Based Research Collective [DBRC], 2003). It is often characterized as “situated in real contexts, focusing on the design and testing of interventions, using mixed methods, involving multiple iterations, stemming from partnership between researchers and practitioners, yielding design principles, different from action research, and concerned with an impact on practice” (McKenney & Reeves, 2013, p. 97-98). The goals of DBR are thus to produce and/or improve innovative learning environments, understand how these environments achieve their (un)intended purposes, and attain some knowledge about teaching and learning. I and others (e.g., DBRC, 2003) see projects that are carried out using DBR approaches as intending to simultaneously (a) empirically evaluate a design iteration of a learning event and/or space while also (b) putting a theoretical explanation for that learning event and/or space to the test. It is iterative and cyclical, as seen here:

Much like general processes of design, I think that DBR draws part of its strength from its adaptability. Researchers employing DBR usually remain adaptive to emerging needs and insights from the research context and/or changes in their own theoretical framing of their work. This is, in fact, part of the reason that researchers in the early 1990’s began to justify the need for a change of research paradigms in education that has lead to popular understandings of DBR. For instance, researchers such as Brown (1992) and Collins (1992) began to present the case for what they called “design experiments”. These had the main purpose of recognizing that understanding of teaching and learning events and/or spaces should not be limited to sterile laboratory-like contexts. Instead, design experiments were a way to account for (instead of controlling for) the “messiness” of the real world because “real-life learning inevitably takes place in a social context, one such setting being the classroom” (Brown, 1992, p. 144). Though the term “design experiments” has mostly fallen out of use, the arguments put forth by such work still constitutes the foundations on which much DBR still stands.

In short, because DBR draws strength from its priorities to both understand, adapt to, and solve problems in real-world contexts, and because I see design in broad terms as the process of devising “courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones” (Simon, 1969, p. 111), I see DBR as a goal-oriented way to provide informed and rational decision making that helps change something from what is to what ought to be. In this case, however, “ought to be” is not meant to be prescriptive; it more closely means “generally improved through increased understanding”. In this way, I align my conceptualization of DBR mostly to that of McKenney and Reeves’ (2013) in that it is not strictly its own separate “methodology”—though DBR has oft-used methodological tools such as conjecture maps (Sandoval, 2014). It is instead a goal-oriented application of any number of methodologies in ways that are intended to solve problems in the world while seeking to attain a greater understanding of those problems.

=====

Resources

Here are a few sources we think are especially helpful to get a quick understanding of DBR, what compelled its emergence, and set the table for you to potentially contribute to what might entice its future developments.

Brown and Collins’ articles from the early 1990s are somewhat landmark pieces that both do a good job of explaining the existing paradigms that DBR was responding to. These serve as a nice way to understand what kinds of things necessitated DBR:

(1) Brown, A. L. (1992). Design experiments: Theoretical and methodological challenges in creating complex interventions in classroom settings. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 2(2). https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls0202_2

(2) Collins A. (1992) Toward a design science of education. In E. Scanlon, T. O’Shea T. (Eds.), New Directions in Educational Technology, 96. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-77750-9_2

Over a decade after the articles from Brown and Collins, Kolodner published this piece that does a nice job of almost narrating a story of not only DBR, but also of the learning sciences–the discipline in which DBR is perhaps most widely used:

(3) Kolodner, J. L. (2004). The learning sciences: Past, present, and future. Educational Technology: The Magazine for Managers of Change in Education, 44(3), 37-42. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44428906

Barab and Squires’ article is highly cited for a reason; it highlights and problematizes some challenges that are faced in carrying out design-based research. Getting insight into these challenges is incredibly helpful for arriving at more in-depth understandings of DBR:

(4) Barab, S., & Squire, K. (2004). Design-based research: Putting a stake in the ground. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls1301_1

The collective provided the argument that DBR can compose a coherent methodology that bridges theoretical research and educational practice, a key reading (and group) to be familiar with for sure:

(5) Design-Based Research Collective. (2003). Design-based research: An emerging paradigm for educational inquiry. Educational Researcher, 32(1), 5–8. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X032001005

The title of this book is very self-descriptive. Bakker’s book is a great way to attain a practical understanding of design research, especially if you are an early career researcher:

(6) Bakker, A. (2018). Design research in education: A practical guide for early career researchers. Routledge. ISBN: 9781138574489.

=====

References

Brown, A. L. (1992). Design experiments: Theoretical and methodological challenges in creating complex interventions in classroom settings. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 2(2). https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls0202_2

Collins A. (1992) Toward a design science of education. In E. Scanlon, T. O’Shea T. (Eds.), New Directions in Educational Technology, 96. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-77750-9_2

Design-Based Research Collective. (2003). Design-based research: An emerging paradigm for educational inquiry. Educational Researcher, 32(1), 5–8. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X032001005

Fraefel, U. (2014). Professionalization of pre-service teachers through university-school partnerships. WERA Focal Meeting. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.1979.5925

McKenney, S., & Reeves, T. (2013). Systematic review of design-based research progress: Is a little knowledge a dangerous thing? Educational Researcher, 42(2), 97-100. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X12463781

Nelson, H. G., & Stolterman, E. (2012). The design way: Intentional change in an unpredictable world – foundations and fundamentals of design competence. MIT Press.

Perkins, D. N. (1986). Knowledge as design. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Sandoval, W. (2014). Conjecture mapping: An approach to systematic educational design research. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 23(1), 18-36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2013.778204

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books, Inc.

Simon, H. A. (1969). The sciences of the artificial. MIT Press

Warr, M., Mishra, P., & Scragg, B. (2020). Designing theory. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(2), 601–632. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09746-9

Leave a Reply