Three Cheers for Process Design!

Process design is creating a set of actions that can be used multiple times. Join the Talking About Design team in three cheers for process design! Bonus process design tool included.

Can you design for collaboration? How about communication? Can you design for productive conversation about controversial topics like politics and racism? These are the questions that Michael Rohd, founding artist of the Sojourn Theater and lead artist for the Center for Performance and Civic practice, explores.

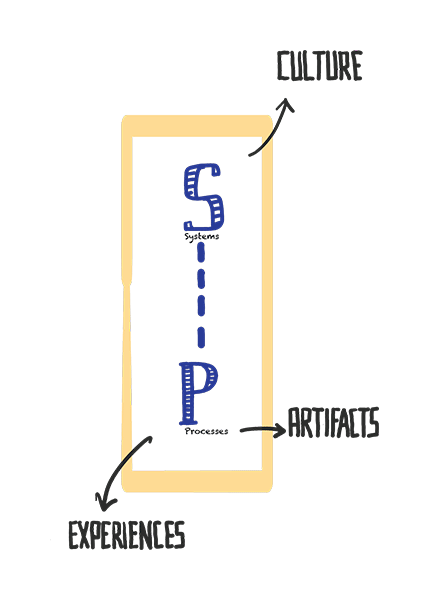

Rohd emphasizes an often overlooked design space: processes. He encourages his students to think about how certain processes may help enact core principles or help participants feel comfortable discussing sensitive issues. For example, one discussion strategy might be to have participants discuss an issue in pairs and/or small groups, and, when ready, larger groups. This Process allows participants to gradually develop comfort for talking about the ideas. Although facilitators create process designs before they are implemented, they often adapt the design in response to group dynamics. The ultimate goal is to enact the process in a way that provides a positive and productive Experience for participants–and that can lead to changes in systems and Culture.

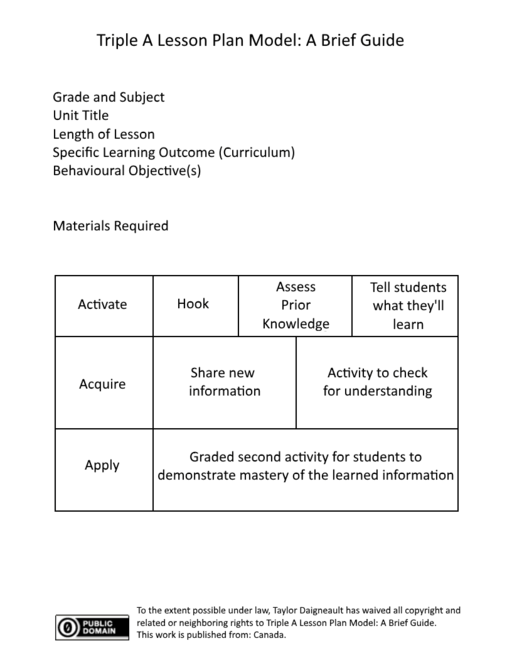

We’ve defined a process as “a procedure or directions that can be used outside of the context within it was created to achieve a goal.” I like to think of a process as an under-specified template (redundant though it is). It’s something that outlines actions, activities, etc. that usually happen many times. Here’s a great example–the design of a hiring process. A lesson plan is another example:

Although we’ve done a lot of talking about design on this website, we have perhaps not given process design it’s due. So join us today in three cheers for process design!

Rah rah process design! Process design supports all design!

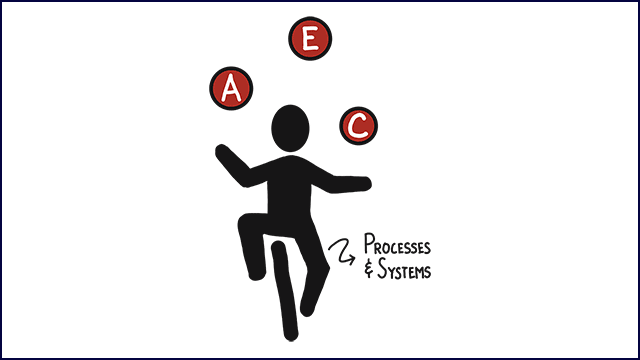

Process design is central to much of what happens in education–it provides a support (along with systems) on which artifacts, experiences, and culture function. Think of our juggler or the systems-processes spine:

For example, teachers often design certain processes (procedures like what to do when you need a potty break or how to enter the classroom in the morning) to make things run smoothly. Experienced teachers set up and practice procedures with students until they became automatic, leaving time and bandwidth for more important things.

Classroom processes are often enacted through artifacts and create experiences. This, in turn, builds a classroom culture. For example, some elementary school classrooms take attendance and lunch counts through artifacts like this:

This is an Artifact, but it reflects a process for taking attendance and designating lunch choices in the morning. The process, supported by the artifact, supports a positive and efficient experience at the beginning of the school day, affecting the classroom culture.1

Not only does process design support all the design spaces, but…

Rah Rah Process Design! Process design scaffolds creativity!

Process designs can actual open space for creativity. Recently Jennifer Stein wrote about how protocols–a type of process–can support creativity. She wrote:

The protocol allows the group to pay less attention to how to have the conversation (group dynamics like who should speak and when or how to say something critical), and to focus more on the what, the content that the group has gathered to discuss. And this, in effect, encourages more focused thinking and creativity.

Let’s consider what this might mean for teachers. I believe their work primarily consists of two things:

- Design–most prominently process design

- Enactments of processes –ultimately a creative and improvisatory act

Let’s take a core piece of teacher work: lessons. A lesson plan doesn’t list everything teachers will do while teaching, but it provides certain topics and activities to be enacted. Some plans provide more detail than others, but the plan is not the lesson–it’s a plan for the lesson (#1 on the list above). It outlines the process the teacher will go through while teaching, but teachers add details and adapt as they go, making it different each time they teach. A junior high teacher might even enact it multiple times (across several class periods) in a single day. The lesson isn’t exactly the same each time–the teacher adapts based on the students’ responses. But the underlying process (as an under-specified template) remains more or less the same. The lesson plan provides a foundation that teachers can create from in real time. It provides structure while leaving holes for creativity and improvisation. It allows teachers to focus on their students and the content instead of worrying about what to do next.

Processes can support creativity. Now, for our final cheer:

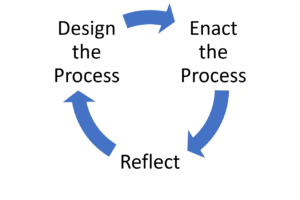

Rah Rah Process Design! Process designs iterate!

The cool thing about process design–particularly when it includes the dimension of adaptive implementation–is that it provides a natural way to iterate and evolve. When processes are enacted several times, each enactment could be considered an iteration of the design. This allows the designer to make ongoing modifications, gradually making the process “more preferred”2 at the same time as enacting it. It models a core theme in design: that designing is learning and that the learning happens through designing. Or, as design scholar Kees Dorst said, a designer “learns his or her way towards a solution” through reflective loops3.

Let’s put it all together. Everyone, now:

Rah rah process design! Process design supports all design!

Rah rah process design! Process design scaffolds creativity!

Rah rah process design! Process designs iterate!

But wait, there’s more…

I created a free tool (see link) to support creative process design and enactment in settings such as classrooms, professional development settings, and community action groups. Feel free to use, reuse, adapt, and share–but please follow the CC BY-NC-SA license.

For an interesting example of the relationship between processes, artifacts, and experiences in the classroom, consider the book “The First Days of School.” The authors provide many examples of how to design the classroom (artifacts) to support procedures (processes) that create positive first days of school experiences for students. ↩

Simon, H. A. (1969). The sciences of the artificial (3rd ed.). MIT Press. ↩

Dorst, K. (2019). Co-evolution and emergence in design. Design Studies, 65, 60–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2019.10.005, p. 66 ↩

Leave a Reply