The Paradox of the Petri Dish, AKA Culturing a Culture

Design is simultaneously intentional and ambiguous. Like scientists with Petri dishes, designers know how to use this to their advantage.

Culture.

Noun

- the arts, customs, lifestyles, background, and habits that characterize a particular society or nation

- the beliefs, values, behaviour and material objects that constitute a people’s way of life

- the conventional conducts and ideologies of a community; the System comprising of the accepted norms and values of a society.

- (microbiology) the Process of growing a bacterial or other biological entity in an artificial medium

the growth thus produced - (cartography) the details on a map that do not represent natural features of the area delineated, such as names and the symbols for towns, roads, meridians, and parallels

Verb

- to maintain in an environment suitable for growth (especially of bacteria)

- to increase the artistic or scientific interest (in something)

Design is intentional. Or, more accurately, designers are intentional. They apply knowledge, skills, and practices to create some sort of change. However, the products of design aren’t complete when they leave the designer’s hands. They continue to shift and change as they are put into practice by the user (Lucy Kimbell1 used the term “designs-in-practice” to emphasize that design is never complete). If this is true of relatively stable, concrete artifacts, how much more is it salient to complex, wicked contexts—those intractable, constantly shifting, one-shot opportunity design spaces like systems and culture? In these contexts, the design space shifts while the designer is working in it. Regardless of the level of complexity, interacting in design spaces has consequences. Whether or not those consequences are intentional is a moot point.

Let’s focus on our most wicked discourse–culture. In some ways, designing culture might be like what microbiologists do with Petri dishes. Scientists begin their Petri-dish practices by preparing a shallow plastic or glass dish with a warm, liquid mixture of ingredients. First there’s agar–that familiar red jelly stuff we often associate with Petri dishes. Then scientists add other ingredients–like nutrients, salt, blood, antibiotics–based on what type of organisms they want to support. Once the mixture has settled and cooled, a live organism, perhaps bacteria, is added to the prepared Petri dish. Then the scientists lets the Petri dish—or, rather, the elements inside of the Petri dish—nourish the organism. As the organism grows and multiplies, scientists can learn more about it. In some cases, they might even add more ingredients to see if they can create something different.

So, what does this have to do with the other type of culture–the one that describes community ideologies, beliefs, practices, and the like? Let’s say that we want to design an innovative school culture. We can’t exactly build culture with our hands, but we can prepare a space and plant bacteria, so to speak, and see what happens. This means that at some level we have to let go of control—although we can create conditions for a culture to form, it will grow and morph on it’s own. However, we can set things in place that can promote or support certain ideas. We can design for certain outcomes. A scientist does this with a mixture of ingredients designed to support specific types of growth. We can do something similar.

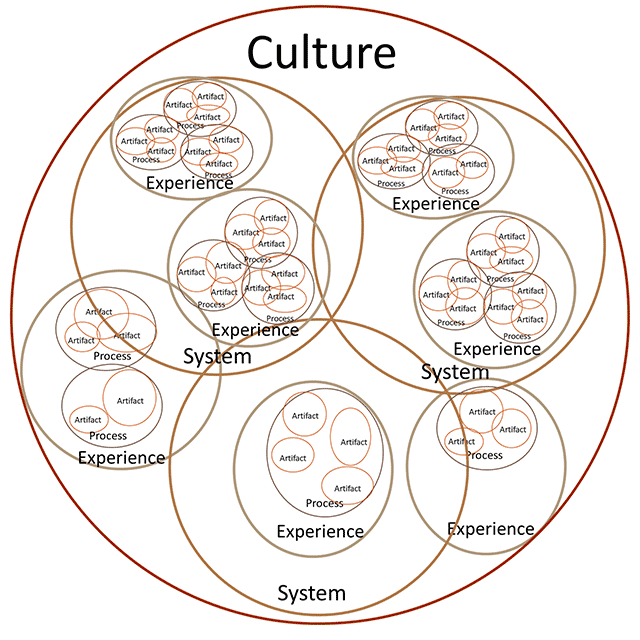

So what are the ingredients? Drum roll, please . . . they are the products of the other design discourses! Artifacts, processes, experiences, and systems. It could also include other cultures, such as a classroom culture that is part of a school culture. These other designed spaces interact and support each other and the developing culture. This is how we can be intentional about cultural design: we are intentional about designing artifacts, processes, experiences, and systems that affect that culture.

The Paradox of the Petri Dish is that we are intentional at the same time as we are releasing control. We are intentional in setting up an environment that promotes certain kinds of changes. But, in the end, we are giving up control–we have to let what happens, happen. Of course, experienced culture designers continually adapt to the results; the design is never finished. Also, unlike Petri dishes that are placed in controlled environments, design spaces are continually affected by outside influences, leading to change whether or not that change is designed. Fighting this type of change is rarely productive, but we can sometimes work with it in creative ways.

In the end, design is about finding those spaces of intentional interaction, watching the results of the interactions, and then responding in productive ways. It is simultaneous intentionality and ambiguity. And who knows, the result might be better than anything you intended.

Leave a Reply