The Flea Circus Fallacy: Jurassic Park and the Perils of Ecological Design

What’s the difference between designing living systems and designing technical artifacts? “Life finds a way” to complexify things…

The 1993 hit movie Jurassic Park touches on a lot of fascinating topics–though you may not think that design is one of them. The thrill and terror of dinosaurs running amok? Definitely. The joy of Jeff Goldblum playing a rock star-inspired mathematician? Absolutely. Humanity’s perpetually doomed attempts to control nature? Arguably, the movie’s big idea! Yet, I contend that this last point is actually deeply related to design and highlights a theme that appears throughout the sci-fi sub-genre of “Frankensteinian cautionary tales”: the folly of designing living systems just like technical artifacts.

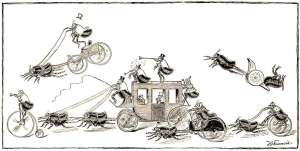

This issue is laid bare by Jurassic Park’s visionary creator and pitchman, Jon Hammond, in one of the movie’s best and quietest scenes (see clip below). Years before getting into the dinosaur-taming business, Hammond ran a far more modest public attraction: a flea circus. From the early 1800s to the mid-20th century, flea circuses were popular sideshow attractions in which fleas were yoked with small harnesses and trained to pull miniature chariots, balance on tiny tightropes, and engage in other feats that demonstrated their proportionally immense strength. Getting fleas to perform was a challenging task, so as technology improved, many circuses became electronically automated: chariots would race, sea-saws would totter, and carousels would spin, all with no fleas required!

As the ringmaster of one of these flea-less circuses, Hammond was ashamed for deceiving people into thinking they saw bugs that weren’t there, and this drove his lifelong desire to create a real attraction with large and spectacular living creatures. With herds of brachiosauruses roaming across majestic meadows, Hammond would never have to rely on illusion again.

Although we might empathize with Hammond’s deep-rooted Impostor Syndrome, it’s hard to forgive his flawed analogy between operating a small, man-made Artifact and managing a large and complex ecosystem. The issue here is two-fold. First, Hammond sees Jurassic Park as merely a “scaling up” of his original flea circus. If we imagine, for a moment, that the park was populated by animatronic dinosaurs rather than real ones, we might be able to partly accept this logic. One could argue that it is only a matter of having more people controlling more technical systems, like the difference between launching a model rocket and the space shuttle.1 Yet, the park was not a purely technical System and, as such, its constituent plants and animals could not be viewed like the components of a machine. In comparison to gears, circuits, or switches, the behaviors of living creatures are extremely variable–even more so when they can interact with each other. This is the essence of the Flea Circus Fallacy. Hammond, having never even worked with a few tiny fleas, failed to realize the impossible challenge of predicting and controlling the behavior of dozens of carnivorous dinosaurs.

While watching Jurassic Park, it’s hard not to have a smug sense of superiority over Hammond: “Don’t you realize that this will lead to disaster!? Didn’t you hear Jeff Goldblum say, ‘life finds a way’?” Yet, real-world scientists, policymakers, and engineers often make the same error and imagine the natural world to operate like a machine. For examples of the Flea Circus Fallacy in action, we need only look to the collapse of ecosystems due to “carnivore cleansing”, the spread of invasive species initially introduced as “pest” control, or the repeated failure of man-made levees to prevent flooding. In each scenario, design decisions in complex, ecological contexts have led to unpredicted and undesirable consequences.

Hammond’s decision to abandon Jurassic Park can be read (perhaps charitably) as an admission that his assumptions about designing living systems were flawed. Yet, the mistakes we make in the real world cannot be so easily ignored. We must learn how to design for complex ecologies and recognize their sensitivity to even small changes. Despite the deluge of bad news about human impacts on the environment, there are some examples of us getting it right–or at least making up for getting it wrong.

Rather than view Jurassic Park as a critique against acquiring scientific knowledge, I see it as a call to more carefully consider how we use this knowledge to design our living world. “An aim,” as Hammond might say, “not devoid of merit.”

1 For an interesting take on the inevitability for problems to arise in all large complex systems, see Charles Perrow’s landmark book Normal Accidents.

Leave a Reply