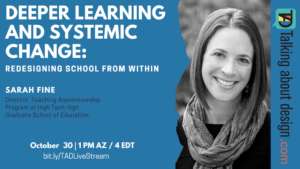

Join us on Friday, October 30th for our next Design Salon with special guest Sarah Fine. Sarah is the Director of the Teacher Apprenticeship Program at the High Tech Graduate School of Education, an educational researcher, and co-author of In Search of Deeper Learning: The Quest to Transform the American High School. The salon starts at 1 PM AZ time/4 PM EDT, bit.ly/TADLiveStream

Haven’t read the book? No problem! Read on for a brief introduction that will kick off our conversation.

What made your favorite teachers stand out? Maybe you had a few who were funny or relatable, gave thought-provoking lectures, or genuinely cared about you and your future. If you were lucky, you might have had one or two who fostered a real connection with a topic, who inspired you, challenged you, and changed the way you saw the world and yourself. Educational researchers Jal Mehta and Sarah Fine argue that this last group of teachers provide students with the rare opportunity to engage in “deeper learning”. In their book, In Search of Deeper learning: The Quest to Transform the American High School 1, they explore a simple question: Why do isolated examples of deeper learning emerge almost everywhere–from private academies to Title I charters– but it is nearly impossible to find entire schools that support it systemically?

Answering this question took Mehta and Fine the better part of a decade, leading them to visit dozens of schools and spend hundreds of hours observing classes and interviewing teachers, students, and administrators. The project started with an optimistic assumption. In 2010, they set out to “to study a range of successful American public high schools…and try to understand what made them tick” (p. 2). Yet, they found that most classes at supposedly innovative high schools with good reputations often looked like classes at more run-of-the-mill schools: students sat passively in desks, listened to teachers “deliver” content, and were expected to regurgitate facts on standardized tests. Faced with this disheartening realization, the researchers changed tactics and decided to do in-depth ethnographic studies of four schools: three that had achieved widespread adoption of deeper learning practices, though in entirely different ways, and the fourth with significant “pockets” of deeper learning.

Answering this question took Mehta and Fine the better part of a decade, leading them to visit dozens of schools and spend hundreds of hours observing classes and interviewing teachers, students, and administrators. The project started with an optimistic assumption. In 2010, they set out to “to study a range of successful American public high schools…and try to understand what made them tick” (p. 2). Yet, they found that most classes at supposedly innovative high schools with good reputations often looked like classes at more run-of-the-mill schools: students sat passively in desks, listened to teachers “deliver” content, and were expected to regurgitate facts on standardized tests. Faced with this disheartening realization, the researchers changed tactics and decided to do in-depth ethnographic studies of four schools: three that had achieved widespread adoption of deeper learning practices, though in entirely different ways, and the fourth with significant “pockets” of deeper learning.

Mehta and Fine’s findings are correspondingly deep and broad, touching on virtually every aspect of the modern US high school Experience, from student dress codes to curricular sequences to teacher professional development. In the book, they seamlessly integrate their empirical data into larger conversations, such as the historical development of public schooling in the US, the institutionalized discrimination that results from course tracking, and the dichotomy (a false one, they argue) between progressive and traditional educational philosophies. The extensive use of quotations from teachers, administrators, and students, along with descriptive vignettes of classroom scenes, keep high-level talk about policy, pedagogy, and theory grounded in real-world experiences. One of the most fascinating– and subtle– insights in the book relates to this connection by calling into question the taken-for-granted notion that school is a System.

In many ways, it seems obvious that schools are systems. Like a combustion engine, computer chip, or nuclear submarine, schools are composed of components that work together using a variety of processes to achieve an outcome. One could point to the flow of students through hallways or the complex programs registrars use to map teachers to courses as evidence of the systemic nature of school. The argument is tempting, but partly flawed. Machine parts and human beings have some significant differences, a prominent one being that humans can reflect on their goals and alter their operations should they choose to. Compared to a piston in an engine, which must function in accordance with its initial design (and the laws of physics), educators in a school have far more flexibility.

So, what makes some teachers operate differently and encourage deeper learning? Mehta and Fine devote an entire chapter to this question, by analyzing seven teachers whose students were frequently engaged in deeper learning despite a lack of school-level support for their practices. In comparison to their more traditional colleagues, these teachers saw themselves, their relationship to their course material, and their students very differently. In the classroom, they often positioned themselves as facilitators of engagement, rather than disseminators of content (e.g. prompting students to think like mathematicians rather than memorize equations). They asked students deep, difficult questions that they themselves might not even know the answer to. Rather than attempting to coax students into meeting artificial standards, they invited them into authentic and rigorous exploration of a topic. In short, these teachers had adopted a “different stance, a different way of viewing what they were trying to do, which came out of their experiences and informed their work” (p. 351).

There are, to be sure, crucial ways that school and district-level policies can foster and encourage these kinds of teaching practices; much of In Search of Deeper Learning is devoted to understanding the few schools in which such structures have been implemented and sustained. Yet, the authors’ research suggests that redesigning the school system will not be like swapping out spark plugs or even building a jet engine from scratch. In addition to making large-scale changes to testing standards, grading schemes, and school accreditation requirements, Mehta and Fine suggest that institutionalizing deeper learning will also require “teachers to rethink what are, for some, fundamental aspects of their identities” (p. 368)”, an act which they term “unlearning”.

There are, to be sure, crucial ways that school and district-level policies can foster and encourage these kinds of teaching practices; much of In Search of Deeper Learning is devoted to understanding the few schools in which such structures have been implemented and sustained. Yet, the authors’ research suggests that redesigning the school system will not be like swapping out spark plugs or even building a jet engine from scratch. In addition to making large-scale changes to testing standards, grading schemes, and school accreditation requirements, Mehta and Fine suggest that institutionalizing deeper learning will also require “teachers to rethink what are, for some, fundamental aspects of their identities” (p. 368)”, an act which they term “unlearning”.

And it’s not just teachers who will have to unlearn the old school paradigm, but also parents, administrators, and everyone else who spent their childhood jotting down notes, staring at blackboards, and cramming for tests. If we want deeper learning prioritized in our schools, all of us–not just teachers–need to unlearn the old system and make mental and cultural space for a new one. While this is a daunting task, it is also maybe easier than we think. We don’t need to invent a new technology or make a scientific discovery to change this system. As the educational luminary, Sir Ken Robinson, (sadly, now departed) stated in a 2018 interview with Edsurge2, “you are the system. You’re it. And I know it’s a complex system. You’re not all of it, but you’re part of it. When you stand there with your children, your class, what you do next is the education system so far as they’re concerned.”

Leave a Reply