Escaping Design Stereotypes: An Interview with Escape Room Designer Andy Parr

Once in a while, our team of writers step back from our conceptual musings to get into what design looks like on the ground. As part of this move, we will be presenting a series of interviews with real designers from many walks of life. First up, Andrew Parr, an Escape Room Designer.

In order to look more in-depth on what it takes to design an Experience, we interviewed Andrew Parr, an extremely successful escape room designer with New Escape Room Designs2 (yes, that’s a job) and general puzzle enthusiast from London, Ontario, Canada. Parr actually started designing escape rooms in his spare time while teaching music at a local high school. However, escape rooms are so popular right now, and his designs are so good, that his side job generates roughly a quarter million in sales each year. He has sold over 600 designs to over 300 clients all over the world yet keeps his job as a high school educator just in case escape room popularity declines.

We are, however, more interested in his design Process than his business success. Think about the challenges presented by escape room design. According to Parr, “the really hard part is trying to estimate how much time someone I haven’t met will take to solve each puzzle. How do you do that? … I’m writing a game that could be played by two people or it could be played by a team of eight.” So, how does a designer of an experience successfully understand and predict how the audience will react? “You just need to guess and hope for the best,” says Parr, “I’m always writing for a team of six averagely smart players who have played a game before. That’s kind of my ideal crowd.”

So Parr does, in fact, write for a particular audience: an ideal escape room customer. He’s not trying to write escape rooms that satisfy everyone. Perhaps experience designers need to select a particular ideal customer group and then, “just guess and hope for the best.”

Parr’s guesses, however, are well-informed by years of puzzle design and puzzle play. Before designing escape rooms, Parr regularly contributed to Games magazine and published a series of puzzles. In short, he has written puzzles for wide audiences before. He knows which have gone well and which have not.

So, how does Parr start to design an escape room? He starts by thinking about things. I expected to hear Parr, a puzzle-writing enthusiast, to mention that he selects certain types of puzzles to begin or that he works on puzzles and then adapts them to the rooms, but he does not. He starts by thinking about the theme and then, most importantly, thinking about the objects attached to that theme.

Parr illustrated, “Well, let’s take a setting like a bank. Like any item you would expect to see in a bank. Let’s think of how that’s going to be a puzzle, like a rolodex maybe. With a Rolodex you can have all sorts of different clues and information and addresses and numbers in there. It’s just a matter of cluing the player to find the right one.”

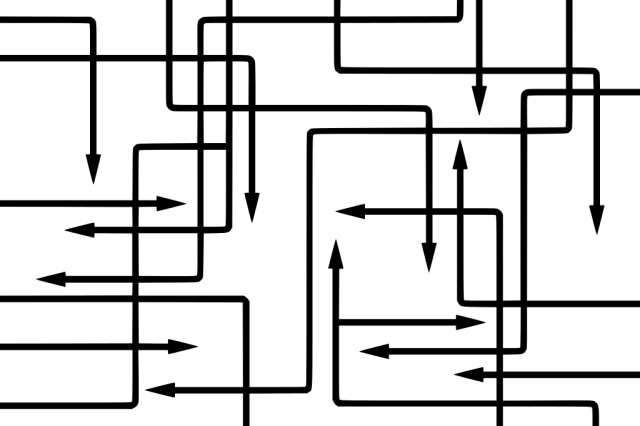

As Parr works, he draws out a flowchart. “I’ve done enough games now that I know that I will sit down with my flow chart and I just make absolutely sure everything’s going to go in the correct order. No clues are going to be given out before they need to be.” He adds, “You need to have a good balance, like scavenging and logic and observation. So, you have a good mix of all these different puzzle types and then it’s deciding the sequence you want to start them off with.” He adds that this flowcharting means that he knows exactly when a design is finished. “I recorded music with my students and that’s the kind of creative project where, how do you know when it’s done? You could have another instrument layer or you could always try something different. I don’t feel it’s quite like that. I put together my skeleton flowchart and so early on, when I’m brainstorming, I’m just imagining a flow chart moving from the top to the bottom of the page with all these squares connected by arrows and there it’s kind of zigzagging back and forth to show how the game has to be solved.” Parr adds, “I know I’m done when I’ve articulated how my customer has to create that puzzle in their room and I’ve articulated what the solving experience will be like for the player. As long as I’ve explained it clearly, that square is done. Move on to the next one.” Essentially, Parr has added his own constraints, in his initial brainstorm, allowing him to finish the escape room design, puzzle by puzzle.

Parr also shows empathy for his customers and recognizes that customers come in with their own preconceptions. “What’s tricky is what makes sense to me as far as a clue relating to a puzzle may not make sense to someone else. Sometimes you have to make things a little more obvious than you’d want to. And players often bring their own assumptions and they make things more difficult anyway.” With designing experience, understanding the preconceptions of your audience is key.

Parr, in general, works alone, with his laptop. He gathers information, constraints, and theme requirements from his client (oftentimes the owner of escape rooms), then gets to work thinking of objects that relate to the theme that can be turned into a puzzle. Then, he draws out a flowchart, with puzzles as the boxes, showing how the puzzles will be revealed and how they will relate. Finally, he works one by one to fill out these puzzles.

But, how do the most creative puzzle ideas come up? “I was desperately trying to get more games up on the website and sitting down trying to write and it’s very difficult when you sit down and say, “I have to come up with this one.” When you put your cell phone away, when you don’t try to work, you just take a break for a while and you just get your head out of work, walk around, go outside, pay attention to what’s going on around you. You just notice things that percolate in your brain and this can become a puzzle. I came up with a puzzle idea when I was walking my dog just from when I saw my dog look a certain way at another dog.” So, Parr has a very specific way of working, but leaves mental space for the creative stuff, when not working. These lead to moments of inspiration that inform his more nose-to-the-grindstone style of working through a flowchart.

Parr, like all designers, combines detailed expertise (e.g., he has written puzzles and games for years to wide audiences, he knows how a group of six averagely smart players would perform on a puzzle) with some practices that may be more universal to experience design (e.g., creating flowcharts to map the user experience, walking around and paying attention to the world in order to come up with creative ideas, or starting with a theme). However, to delve into what makes Parr a designer of experiences (as opposed to a designer of Culture or artifacts), we must examine his focus. As Parr emphasized, order and flow take a paramount position when designing an experience. So, despite the fact that Parr designs artifacts, like the bank rolodex filled with clues, his focus is on the experience and how one clue leads to the next. The rolodex is arbitrary. Another bank-themed puzzle Artifact could fulfill the same purpose. What matters to Parr is that the theme is maintained, and the clues are released in the right order with the right mix of puzzle-type.

I hope this post helped shed some light on the practices of an actual designer. Our posts can sometimes present theory, or tell stories, but interviews grounded in practice can illuminate some of our ideas as well. Also, before I go, I want to thank Andrew Parr for sitting down with me to discuss his business, his puzzles, and his way of working.

2 https://www.newescaperoomdesigns.com/

3 “Flow Work Planning Control” is in the Public Domain, CC0

Leave a Reply