Designing for Systemic Change: Self-Driving Cars?

Can designing systems be done piece-by-piece, or does it require revolutionary design?

Let’s start with two parallel stories of automobiles.

Story 1: Waymo

In September 2012, Sergey Brin, a Google executive tasked with leading Google’s autonomous vehicle program, suggested autonomous cars would be available to the public in five years. Five years and three months later—December 2017—Waymo’s (Google’s self-driving car division) CEO John Krafcik shared a video of autonomous vehicles on public streets, running without drivers. He described how Waymo was testing fully autonomous vehicles. At the time, analysts expected public use of autonomous vehicles by 2020, but Krafcik claimed the technology already existed and was implemented in the Phoenix Metro Area. I had moved to that Phoenix Metro Area—Tempe, Chandler, and Mesa, Arizona—several months earlier. Autonomous vehicles were everywhere, with one catch: technically they were not autonomous. They always had safety drivers behind the wheel.

Now it’s 2020, and Waymo cars continue to be seen in my neighborhood. However, despite continuous reports that Waymo will soon be removing safety drivers from the vehicles, I have yet to see one without a safety driver (note, others have reported that the cars are going driverless).

Story 2: Mazda and Honda (and Toyota and Tesla)

In September 2012, I was driving an ordinary, 2005 Mazda 3 around. Unlike Sergey Brin, I didn’t think much about self-driving cars. But there were at least two things my car did without me. First, it could keep my brakes from locking, increasing traction in emergencies despite my tendency to jam the brakes (what we call anti-lock braking systems or “ABS”). Second, it could maintain a speed without my intervention (or cruise control).

Five years later, I bought a 2016 Mazda 3. In addition to anti-lock brakes and cruise control, it included features that helped me monitor my surroundings: a backup camera, blindspot monitoring, and warning sounds that (annoyingly) did their best to keep me from backing over a pedestrian or crashing into a car in my blind spot.

Now it’s 2020. My parents recently bought a 2020 Honda CRV. Their car not only has anti-lock brakes, backup beeps, and blindspot warnings—it can also automatically engage the brakes when it senses a collision coming. Its cruise control keeps the car inside highway lane lines and modifies the car’s speed to maintain a selected following distance. These “driver assistance” features make it seem like their car is basically self-driving.

What’s the Difference?

While cars with driver assistance features are already on the road and impacting the driver Experience, Waymo continues to struggle to fully implement their autonomous vehicles even within a small geographic area. Why is Waymo having such difficulties? It comes down to systems and systemic design.

Driver assist features can be implemented in a relatively isolated manner. The features occur at the Artifact level–they are changes to the car itself and have a limited impact on what happens outside of the car. Fully autonomous vehicles, on the other hand, are not only about the car technology (the artifact), they also require change on a systems and cultural level. They require coordinated interaction of many systems—road design, transportation laws, and the transportation System as a whole, as well as a shift in cultural attitudes about computer-run vehicles.

For example, technologists claim that one of the most difficult tasks of self-driving cars is not even about the car itself—it is to redesign roads created for human drivers (and the humans on those roads!) An article in the Harvard Business Review claimed:

The key question we should be asking is not when will self-driving cars be ready for the roads, but rather which roads will be ready for self-driving cars. (emphasis added)

The safety and navigational elements on today’s roads are designed for human drivers. They assume human eyes will see the lights and human brains will interpret the signs. However, autonomous vehicles would be better supported by standardized infrastructure, radio signal-emitting traffic signals, and systems that allow vehicles to communicate with one another. These elements are part of a larger transportation and safety system, and changes would need to be widespread to be effective.

Self-driving cars also impact a different type of system that links to Culture. Currently, most self-driving cars support rideshare-like service: riders can request the car when they need to go somewhere. But most of the cars on the roads are privately owned vehicles. Although other rideshare services have made sharing cars more common, in order for self-driving cars to truly become integrated in the transportation system, they need to either match the convenience of owning a car or change the cultural expectations surrounding automobile transportation.

Wide-spread use of autonomous vehicles requires other cultural shifts—riders must feel safe both inside and outside of the vehicles. Sitting in a vehicle that moves itself can be a bit unsettling—even a 2018 video from Waymo shows riders nervous about riding in a car without a driver. This isn’t to say this can’t be overcome (in fact, we might someday have the opposite problem as demonstrated in the video clip below); a similar phenomenon presented itself when automatic elevators entered the scene–but it took 50 years for the public to become comfortable with riding on a self-moving platform.

Citizens must also be comfortable outside autonomous vehicles. Although human drivers might present more danger to pedestrians than computers, people are unforgiving of errors in self-driving car systems. Gill Pratt described that people demonstrate more empathy towards accidents that are the result of a human driver than they do for computer error (or perceived computer error). Sadly, in 2018 an Uber self-driving test car hit and killed a pedestrian just down the street from where I live. The accident was eventually attributed to human error (the safety driver was enjoying the evening’s broadcast of The Voice instead of watching for pedestrians crossing dark streets; the pedestrian darted out in front of the car in the dark), but Uber and the State of Arizona were criticized for not paying adequate attention to self-driving car policies and procedures. Uber ended its test program in Arizona.

Evolutionary and Revolutionary

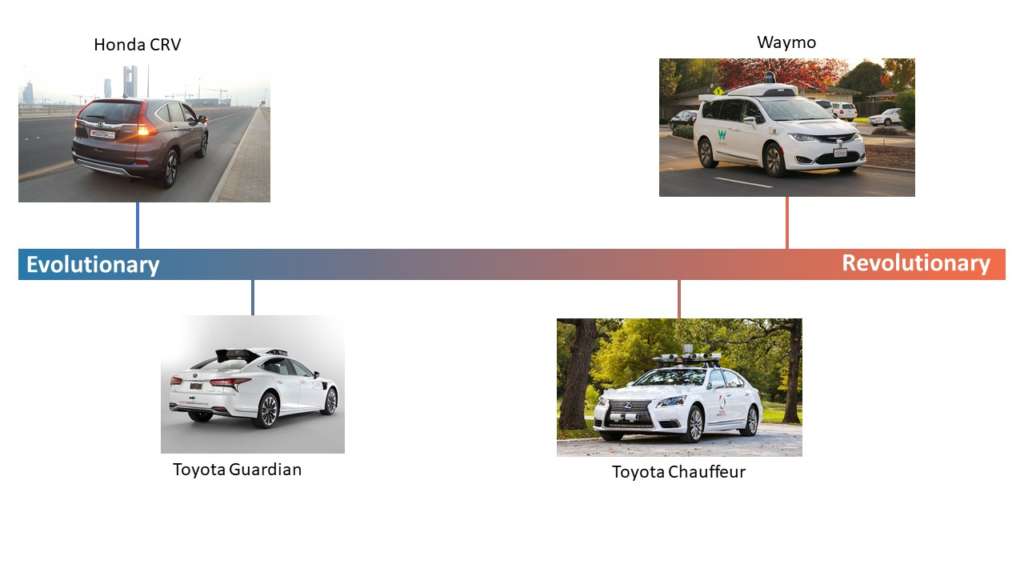

One way to compare the progress of self-driving vehicles is by considering the type of design processes. Are the designers striving for evolutionary (step-by-step) improvements, or revolutionary (complex, all-at-once) shifts? If we imagine a spectrum ranging from evolutionary to revolutionary design, Waymo is on the revolutionary end.They are focused on a whole system of autonomous cars, including how cars operate as part of the whole transportation system. My parent’s Honda, however, exemplifies evolutionary design by gradually introducing monitoring and self-driving features.

Toyota is approaching design from both ends. Toyota claims to follow the policy of “kaizen,” or making vehicles incrementally better each day, an evolutionary design approach. However, in 2019, they announced the design of two types of autonomous cars: Guardian, which includes self-driving features that enables the car’s computer to work with the driver, and Chauffeur, a car designed to be fully autonomous. Engineers suggested the Guardian might be purposefully designed to acculturate drivers by starting with minimal features but ramp up control as drivers become accustomed to the new driving experience. This gradual approach brings self-driving technology into existing systems and cultures, making it an easier fit. On the other hand, Chauffeur seems to be the goal of a more revolutionary design Process, similar to Waymo.

Evolutionary OR Revolutionary?

So. Which is better: revolutionary or evolutionary design? Waymo believes revolutionary design is needed, but writer Andrew Hawkins isn’t quite sure:

Waymo has long argued that driver-assistance technology like Tesla’s Autopilot will just exacerbate the problem. Only by completely eliminating human involvement can we be assured that driverless cars are safe, they argue. But is Waymo getting around this problem by removing the driver, or actually creating new complications altogether?

In other words, driver-assistance technologies are not really changing the system, and attempts at small changes without addressing larger systems might be counterproductive. However, Waymo’s revolutionary approach might result in unforeseen complications.

Let’s break it down a bit more.

The Argument for Evolution

In evolutionary design, the designer can continually adapt to what happens when designs are implemented. It’s like prototyping, with each prototype making its way to the market for real-world testing. Changes that don’t work can be tweaked for a better fit. If new features are added a piece at a time, it’s easier to see their effects and make adjustments.

In revolutionary design, full implementation requires all elements of the system to work together. Although pieces of the design will likely be created through prototyping, the prototypes are not designed to work in the real world. This limits the designers’ ability to evaluate how the elements of the design will work in a larger context. Then, when all elements are implemented at once, the designer may struggle to isolate the effects of individual elements. As Andrew Hawkins wrote, designers might unintentionally create new complications. Worse, if something doesn’t work, designers may have to start from scratch.

The Argument for Revolution

In evolutionary design, changes are made to fit within the current system. Each element brought to market must work within the current system, and saying something “doesn’t work” usually means it doesn’t work in the current system. Such a process might keep us stuck in a box. In the end, truly changing systems will likely require a leap out of the box.

In revolutionary design, change begins and ends at a systems level. Designers are free to imagine new systems. In theory, their work doesn’t have to be implemented in what is available today. Revolutionary design enables new types of thinking and working. It supports throwing away the box and creating something entirely new. But, eventually, something has to be implemented–and the implementation might require larger changes than other systems seem to allow.

For example, I have an app that allows me to use Waymo self-driving cars. However, despite being offered a few free rides, I have yet to try it out. Although Waymo is attempting a relatively complete implementation of their model, it does not actually change the system enough to make it useful to me. The area Waymo cars run in isn’t large. I live on the north end of the boundaries, and, as luck would have it, my daily transportation is almost exclusively heading north, in an area where Waymo doesn’t yet have permission to operate. My trips south are mainly recreational and usually include a friend, but my friends can’t ride in Waymo cars because they are not part of the early-adopter program. For every day trips, such as grocery runs, I prefer to drive myself. Although, theoretically, Waymo is attempting revolutionary design, practically it has to take some smaller (evolutionary) steps to meet legal requirements and policies. And the evolutionary implementations seem to struggle—perhaps because Waymo designed their technology to exist in a different kind of system.

On the surface, evolutionary design of autonomous vehicles seems to be making more progress. Such designs actually impact the driver experience today, while Waymo seems to be floundering. But what about long term? Will evolutionary design (like my parent’s Honda) ever lead to significant systemic change? Let us know what you think in the comments!

I really like this take on AVs. In my world a common debate is something like, “AVs will solve all of our problems because they’ll eventually eliminate the need to own a private vehicle and reduce all kinds of negative externalities that result from driving” vs. “Even if people buy into such a system over time, we will not see the livability of communities improve if we continue to rely on limited-capacity vehicles because they take up so much of the public space that could be used for better and higher uses.” It’s like both sides want revolutionary change, but there are inherent conflicts between the two.

I guess my point is another wrench in things is when humans don’t agree on what the best outcome is in the first place, much less whether change should occur revolutionarily or evolutionarily.

Nice last name! 🙂

This is a fabulous observation and something we should think and write more about!

In design we talk about wicked problems–complex and intractable problems, the type where people don’t agree on what the problem is, let alone the solution. My favorite quote about it: “The problem can’t be defined until the solution has been found. The formulation of a wicked problem is the problem!” (Rittel, H., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4, 155–169. p. 161).

The challenge with wicked problems is just what Rittel and Webber said there–the solution itself defines what the problem is. So if AV’s are the solution, then the problem is that there are too many “negative externalities from driving.” But if the problem is livability and public space, then we have to look for other solutions. Part of the challenge here is that, right or wrong, technologies define problems from the perspective of the designer/technologist. If I’m Tesla, I frame the problem a certain way because of what I see and how I think all the time (on top of the available market share if I can define the problem a certain way…). And if I can come up with a convincing new technology, I have a lot of power (vs. those who see a different problem but don’t offer up a convincing solution).

One way to find a more equitable way of defining problems and solutions: recently Areej Mawasi wrote a guest post about co-design (https://talkingaboutdesign.com/de-centering-the-researcher-ten-reflections-on-co-designing-with-local-communities/), a way to start to address some of these disparities. She calls for involving a wide diversity of community members to address different values and perspectives. Also: “Do not start from technology solutions—listen and identify needs and problems in collaboration with people.” Sadly, when we are talking about commercialized products, this rarely happens because the designers start with a certain technological mindset.

And–if you’re into transportation, as I know you are!–you might like Amanda Riske’s post: https://talkingaboutdesign.com/case-study-the-new-york-city-subway/