Case Study – The New York City Subway

This case study dives into the design and redesign of the subsystems that make up each rider’s journey through the Big Apple.

When visiting New York City the MTA subway is unavoidable. It does not take long for visitors to feel that the MTA is both extremely convenient (e.g., it goes everywhere), but also extremely inconvenient (e.g., sometimes you have to wait to go anywhere at all). When I lived in NYC, sometimes the MTA whisked me away to my destination in a New York minute and other times I was stuck sweating on a steamy platform. In fact, the stations are so notoriously hot that the group Improv Everywhere comically turned the 34th street platform into the 34th Street Spa on a summer day. The platform was 10 degrees hotter than the street above1 so the Improv group hung signs renaming the platform “34th Street Spa” and handed out moist washcloths while offering backrubs to MTA customers waiting for the train.

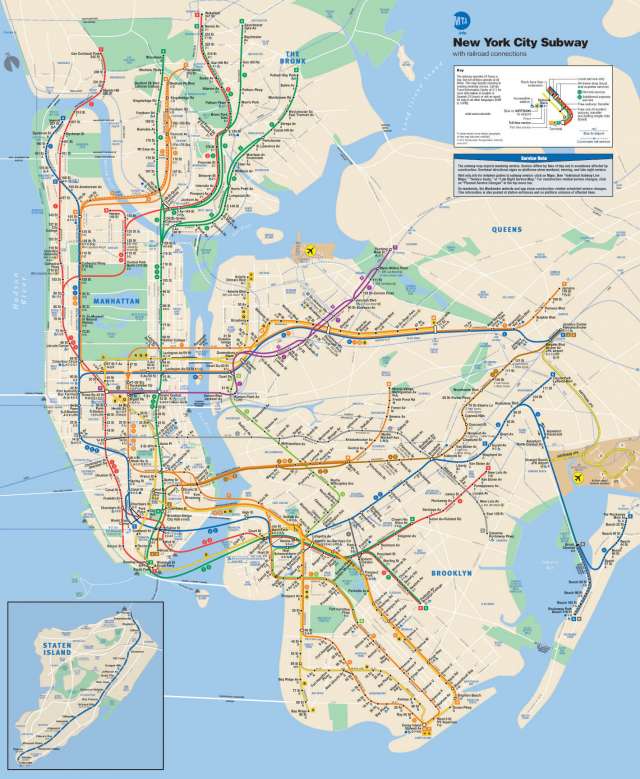

Though the 34th street platform suggests otherwise, this metro System is meticulously designed. Think about the magnitude of the task. The subways mobilize millions of citizens and tourists, transporting them throughout the five boroughs. The sprawling networks of tunnels, tracks, and trains are set to a schedule, creating a complex system. The rider’s journey to the train involves artifacts (tickets), processes (boarding the train), and experiences (waiting for the train and riding the train) within the system so the rider gets to where they want to go. Yes, it’s easy to make fun of the hot subway platforms, but considering the scale, history, and logistics, it’s amazing the system functions at all.

The history of the MTA is not unlike its trains, full of starts and stops (See NY Times interactive map for a fascinating visual history). In the 1970’s, ridership shrunk to half of what it was in the 1940’s due to poor maintenance and shootings on the trains. During the 1980’s two major events improved the MTA. One, the system obtained funding for air conditioning on the trains. Two, crime decreased due to “crackdown on fare evasion”2. The ridership increase continued until 2017, but that caused its own problems. So, in 2017 New York Governor Andrew Cumo declared a state of emergency for the MTA calling out reliability issues and crowding problems. In 2018, Andy Byford was hired from Toronto Transit Commission as the new president of the NYC MTA to retool the system. Since taking on this role he has made some movement toward his goal “to make the trains run on time”3. In 2019, the 79% of the trains were on time compared to the 60-70% for the previous 7 years4. However, the system that Byford acquired was riddled with issues including ineffective materials, confusing processes, poor customer Experience, outdated operations, low morale among riders, and yes, hot platforms.

To improve the overall system, Byford is trying to understand the depths of the problems by considering all of the moving parts of the subsystems. The subsystems account for the logistics of trains, stations, people movement, and information sharing. All of which is situated within a major city which can add even more complexity. For example, The New Yorker reported that one day, the MetroCard vending machines in forty stations malfunctioned making it impossible for customers to purchase tickets. Only one IT person understood the root of the problem: a subprocessor needed rebooting. However, the problem was prolonged since the single IT worker was in the middle of a long commute home to New Jersey when the problem struck.

It seems illogical for only one employee to have the skills to debug the ticket machines, but those flaws are exactly what Byford himself is debugging. He works and designs at scale. Byford addresses issues systemically by training workers in new skills, creating new positions, and rethinking shift schedules. He thinks about solving problems by finding and training others to solve the problems. He also facilitates ways to get the right people in the right place with the right information.

For example, to address customers’ experiences and needs, he hired Sarah Meyer as chief customer officer, a brand new position focused on understanding the customer experiences and implementing improvements to the system from the customer’s perspective. Meyer rides the subways and buses with the purpose of noticing what might frustrate customers. Her immersion in the rider’s experiences allows her to preemptively make changes to the system, improving the customer experience. One such improvement: She relocated the Lost and Found to a more prominent place because it was ironically hard to find.

Updating a system that is underground and 100 years old has a variety of challenges. Trying to update such a train system, unlike updating a piece of software, has very physical challenges like a limited tunnel size or platform real estate. New creative ideas, like hiring a chief customer officer, cannot always overcome the limits of a system designed in a different era. Though Byford should ideally improve the system for all subway-goers, he seems to have failed for at least one group. The renovations or “station renewal” planned for 2021 faces push back and possibly lawsuits from disability rights groups for not expanding access to riders that use mobility devices5. The MTA is planning on spending $100 million to update stations in Queens but no ramps or elevators are planned to increase access. This is just one example of the design failures of Byford, which are just as important to highlight as the successes.

This case study shows the sheer scale Andy Byford must consider while fixing the MTA system, and it isn’t as simple as getting the “trains to run on time.” The system is interconnected and requires organization of scheduling the trains and workers, signals, track networks, and the Process of riders boarding the trains, to name a few. In other words, to improve the system, Byford must think big. He must think about how to train or hire or deploy workers to solve mechanical issues. He must also think about the priority of the system to provide a good customer experience and access for all riders. Hence, he must design systems that do not just work in a utilitarian way, but also show empathy and embrace the diversity and Culture reflected in the locals and the visitors in New York. Byford must design a system that (like the other important New York landmark) welcomes the tired, the poor, and the huddled masses yearning to find home.

Todd, Charlie. (2014). The Subway Spa [YouTube]. New York City. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=agUF_53fmyw ↩

Finnegan, William. (2018, July). Can Andy Byford Save the Subways? The New Yorker, (July 9 & 16, 2018). Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/07/09/can-andy-byford-save-the-subways ↩

Finnegan, William. (2018, July). Can Andy Byford Save the Subways? The New Yorker, (July 9 & 16, 2018). Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/07/09/can-andy-byford-save-the-subways ↩

(2019, September). Is the New York Metro Great again? The New York Times, (Jan. 18, 2019) https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/16/nyregion/mta-subway-nyc.html ↩

Offenhartz, Jake. (2020, Jan. 15) “What’s Stopping The MTA From Reopening Its Locked Subway Entrances?” Gothamist, Gothamist, gothamist.com/news/locked-staircases-mta. ↩

Leave a Reply