What is (and is Not) Design?

Design, at its core is about intention. Design is an intentional move toward a more preferable solution, regardless of the concreteness of the final product.

Short Answer:

From designing classic computer icons to winding lines at disneyland, we argue that design, at its core is about intention.

Long Answer:

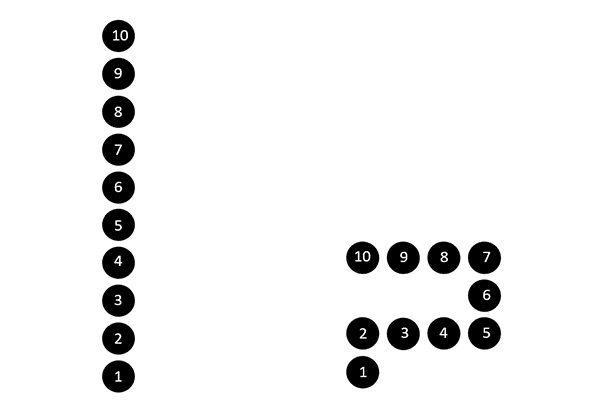

In 1983, Susan Kare launched a set of icons that would make an icon. Subscribing to a personal policy that every pixel matters, she created the first icons to adorn the Mac interface: smiling little computers and little hard disks that universally mean “save” to every person on the planet with a computer. Kare is responsible for the font of the iPod, Chicago, an elegant, yet pixel-heavy font that seemed to match the style of the iPod itself. She is, to the core, an exemplar of modern notions of design.

Kare, however, represents just one type of design. We know that what she does is design. But what else counts as design?

Design, at its core–at its beating heart–is about intention. Cut design and it will bleed intention. Designers are actors who intentionally change something for some purpose, like changing the color of a teapot to calm the user or changing the spout to pour without dripping back on itself. When designing street signs, for example, the design must communicate quickly to a diverse group of citizens. The “look” sign pasted in many cities around the US uses eye icons, large arrows, and a contrasting black and white color to quickly and universally warn pedestrians to peep left and right before crossing the road. The icons, the colors, and the size were intentionally selected to enhance clarity. They change the existing situation–a dangerous street–to something more preferred: a safer street where pedestrians look before they leap. To quote a famous designer, Herb Simon, “To design is to devise courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones.” Designs start with intention and finish with problem solving.

If design is about intention, many actions fit the mold. One can design something concrete, like concrete, for example (or a teapot or a street sign). Or one can design something less concrete like an Experience which Bruce Sterling describes as “the most imperial, most gaseous, most spectral form of design yet invented.”[1]

Think about the design of lines at Disneyland. The designers (err… “imagineers” in Disney parlance) use, and sometimes design, artifacts in the service of experiences. But they mostly design experiences. In fact, when horrendous queues were wreaking havoc on the happiness of park goers in the late 50s, Disney imagineers invented a new type of queue, the switchback queue, which targeted park-goer experience above all else.

This simple change, revolutionary at the time (in fact, Wendy’s, American Airlines, and Citibank all stake claim to the invention),[2] did not change the actual length of the line or the waiting time. However, instead of one long line where guests don’t see each other’s faces, they redesigned it as several short-looking lines that fold around each other, with the added benefit of “people-watching”. Behind this choice was intention–a critical aspect of design.

This redesign made lines more conducive for interactions with other guests. In other words, despite waiting the same amount of time, the experience of waiting in line made guests happier because the imagineers disguised its length and provided opportunities to socialize face-to-face with other guests while waiting. The new queue could be a considered a designed Process that was enabled by new designed artifacts such as line guides. However the genius wasn’t in the process or supporting artifacts. It was in how it changed the experience.

Design encapsulates any type of intentional move toward a more preferable solution, regardless of the concreteness of the final product. Naturally, this means that design encapsulates a lot, but not everything.

In the previous paragraphs we expanded the notion of design, but there are limits. Some things feel designed, but actually do not fit our definition above. They are not intentionally designed. For example, if Mother Nature, over generations, selects birds with the best-adapted beaks for getting fruit, is that an “act” of design? Depends on whether or not you believe a sentient being made an intentional choice to solve a problem. If so, then yes. If not, then such a beautiful “design” is only a “design” to a poetic mind. In a nutshell, design is about intentionally changing something in a way that could persist.

1Sterling, B. (2009). Design fiction. interactions, 16 (3), 20-24.

2https://slate.com/business/2012/06/queueing-theory-what-people-hate-most-about-waiting-in-line.html

Leave a Reply